Buckminster Fuller often noted that that we have enough wealth and technological capacity for everyone in the world to live in abundance — if we would only collectively decide to it. As he put it, we have within us the capability “to make the world work for 100% of humanity, in the shortest possible time, though spontaneous cooperation.” At this historical moment, when the world has been brought to its knees by global pandemic, economic downturn, racial injustice, and political strife, such optimism seems naïve. And yet, even without access to the vast calculations for which Fuller was famous, there remains something intuitively true about his sober conviction on this point. Anyone who has a sense, deep down, that society could be working better, knows what I am talking about.

As an urban planner, much of my thirty-year career has been focused on the systems and infrastructure we need in society to undertake such large-scale economic distribution. I have worked with school districts, colleges, and employers on workforce initiatives; advised local government agencies and planning commissions on equitable development; and organized teams at financial institutions and supermarket operators to open branches or grocery stores in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty. All of these efforts have sought to address the economic divide by changing the systems through which basic products and services are brought to people in their everyday lives.

But as fruitful as these efforts have sometimes been, they have often felt unnecessarily laborious, grindingly slow, and deeply resisted by people who are afraid of change. That’s partly because they often depended on a few people to do the heavy lifting. And that has just never felt completely sustainable. Moreover, the inherited infrastructure on which we graft these changes is typically made up of entrenched bureaucracies. Navigating them has entailed understanding the hierarchies of leadership, the divisions of roles and responsibilities; and the organizational cultures, protocols, and practices. I have seldom seen evidence of the “spontaneous cooperation” that Buckminster Fuller envisioned.

And yet I hold with certainty to the idea that it is possible. One reason I do involves a Christmas story that is little known to many people today. It started in 1912 in the James M. Farley building of the United States Postal Office in New York City, a grim, imposing building directly across Eighth Avenue from Penn Station. It is a building whose vast size and granite columns could not more perfectly exemplify the control and inflexibility built into modern bureaucracies. The story concerns an unlikely man, Frank Hitchcock, who some might say embodied the principles of command and control institutions. As Postmaster General he aggressively prosecuted mail fraud, and he led the development of the country’s airmail service.

In December 1912, however, Hitchcock became aware that his postal workers were becoming preoccupied with what at first seemed to be a relatively inconsequential topic: what to do with the avalanche of letters arriving in the post office addressed to Santa Claus in the North Pole. Most letters had return addresses, which conscientious post workers recognized as tenements on the lower east side or in other poor neighborhoods across the Burroughs. Hitchcock made a rather extraordinary executive decision, one that that ran counter to all conventional training of postal workers: he authorized them to open and read the letters.

And he didn’t stop there. Under his leadership, New York’s postal workers began creating and maintaining a vast record-keeping system. Children’s names and addresses were painstakingly noted in ledgers with details on the toys they had requested: wooden hobby horses, wagons, tricycles, model trains, tin soldiers, Teddy Bears (popularized a decade earlier by Teddy Roosevelt), Campbell Kids dolls (manufactured by the soup company starting in 1909) or the new Kewpie dolls. Lists of requested toys and quantities went out through informal associations and networks in New York’s middle class and affluent families, as well as civic and charitable societies. Toys were purchased, boxed, wrapped, and delivered to the James Farley building, where postal workers affixed the appropriate labels and handed them off to deliverers. The initiative has continued to the current day and expanded nationwide. In fact, the US Postal Service has declared that 2020 is the first year that “Operation Santa” is national.

What is significant about this strategy — and what always stays with me– is that it created opportunities for large numbers of people to participate meaningfully in a bold crystallized vision. In this case, it is a vision propelled by the archetypal ideal of Santa Clause, the principle that there is a higher intelligence in humanity that can figure out to how to give everyone what would make him or her most happy. To be sure, such a system would not work without the bureaucratic infrastructure of the United States Postal Service as a coordinating entity and delivery apparatus. But nor would it work through bureaucracy alone. The creativity, ingenuity, and sense of responsibility are distributed widely.

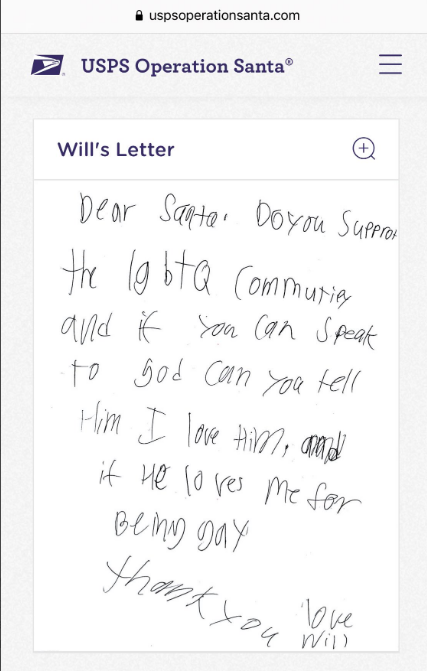

In a new documentary, “Dear Santa,” filmmaker Dana Nachman interviews an Operation Santa volunteer, Michael Munoz. Michael, who is gay, read a letter from a little boy who had not asked Santa for a toy, but simply asked him if he loved gay children. Michael mobilized dozens of his friends to pull together a pile of books and materials that would show the little boy how loved he was by a community he had not even met yet. As I recall childhood T.V. shows about Santa Claus, they usually depict him as an wise man who seemed to know about every child’s conduct and needs. But I never saw one Santa depicted who could have pulled off what Michael Munoz did.

And that really was Buckminster Fuller’s point. If humanity ever decides to collectively deploy the intelligence and compassion of every person, it will be as if we have once again discovered fire. And I, for one, think we will get there.