One of the world’s most beautiful and intelligent birds lives in a few select areas of Brazil, but only three populations of the Hyacinth Macaw remain in the wild. One of these habitats occurs in remote Piaui State of northeastern Brazil, only a few hundred kilometers from the beaches, bars, and whorehouses of Bahia, but in a world completely apart. The Hyacinth macaw prefers the dry forest regions of the country and these forests, not as sexy or internationally famous as the Amazon, are disappearing at an alarming rate, their wood cut for lumber, their trees cleared for cattle farms, and the soil utilized for growing soybeans. With this competition for space and resources, an inevitable decline in macaw populations has begun.

1) Pristine dry forest in Piaui

2) Red cliffs in the distance; Hyacinth macaws nest in these

In addition, as the largest of the macaw species, the birds are highly sought after as pets and bring five-figure prices on the open market. Their feathers shine with brilliant and psychedelic hues. Best of all, and unlike other macaw species, they can be domesticated as adults.

Traditionally, Brazilian hunters have trapped them for sale on the illegal market, shot them out of the sky for sport, and laid waste to their nests in search of eggs, which are supposed to be a delicacy. As the birds only nest on remote cliff-sides, this human activity comes with a certain amount of risk.

4) Hyacinth macaw nesting sites

During the 1990s, Dr. Charlie Munn, in cooperation with a local NGO, set out to preserve one of the last habitats by training former hunters to work a tourist guides and conservationists. A small camp was constructed near a convenient access point to the local forest. The camp was primitive but serviceable.

5) A local homestead. Piaui is a desperately poor region of Brazil.

6) Honey-gathering; one of the few ways for locals to generate income

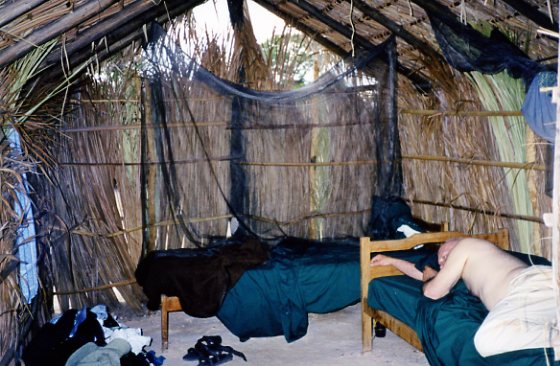

In the interests of having tourists stay in a local-type setting, a few small thatched bungalows were built, all serviced by crude outhouses.

7) The original camp

8) My own cabin. The structure had no doors, only cloth curtains to facilitate a modicum of privacy. One night I felt an animal jump on the foot of my bed. I hastily switched on a flashlight and saw a frightened kitty cat, shaking with fear. The next morning we discovered prints of Maned wolves around the cabin. Clearly the cat thought that we could protect it; I am no sure what I would have done had a wolf strayed into the cabin.

Years later I hear the infrastructure at the camp has improved dramatically and that groups visit the macaws every year.

9) Dense bush near the camp

Macaws should not be kept as pets as they can live upwards of seventy years, and who wants the equivalent of a four-year old kid in the house for that long? Anyway, these magnificent creatures belong in the wild, not in our houses and apartments for the benefit of our selfish amusement.

My last interaction with Hyacinths in Brazil was the most intense one. We had a blind placed near the camp, about a twenty-minute from the cabins. Here we sat for 20 hours during a three-day period, watching the birds warily descend from the trees to eat ground nuts that were brought to the location in pick-up trucks. We’d been told specifically never to leave the blind, as this action would spook the birds. On the last day, being my usual resistant self when taking orders, I decided to exit the bamboo shack. As one, the macaws rose from the ground and furiously swirled and dove, as if challenging me to a duel. The experience was quite frightening, but gradually the birds realized that I was not a threat. They began to fly alongside me in great looping motions, cocking their eyes to see me better. I put on my warmest smile and waved, having now made friends with one of the planet’s most endangered avian species.

10) Brazilian dry forest. Soon this too will have disappeared along side its neighbors to the north and west, the Amazon basin rain forests.

Strange as it may seem, I was never tempted to photograph the birds; it was as if to do so would be to intrude on their privacy. They deserve to live unmolested lives as much as ourselves, an increasingly futile task in the modern world.