-Wilfred Thesiger, Arabian Sands, 1959

My son Walker wants to join me on an adventure in Morocco. I propose a rash undertaking, a trek to the Riff Mountains, the Mediterranean coastal range where the grass is greener, so they say… Not many tourists yet venture here. Yet it has one of the highest mountains in North Africa, Jbel Tidiquin, 8031 feet above the sea, and I would love to climb it.

We team up with a wonderful driver, Ahmed El Abdi, who takes us first to Tangier for the night, where we are given the room, we are told, used by Bernado Bertolucci when he filmed his version of Paul Bowles novel, The Sheltering Sky. It has a dark-wood chair inlaid with fragments of mother-of-pearl that is exquisitely uncomfortable. Adjacent is a fine bureau with tooled cabriole legs, and when I open one of the miniature drawers there is a scrap of crumpled paper with illegible scrawling…and I wonder if this might be some script notes from the mind of a genius filmmaker.

It reminds me of a moment some years ago when I stayed at Francis Ford Coppola’s Blancaneaux Lodge in the glazed hills of Belize. It was during the off-season, and the eco-resort was near empty, so the manager offered that I stay in Francis’s private bungalow. I looked around his room and saw portraits of his extended family, including Nicholas Cage and Sofia Coppola; piles of scripts, and notes scribbled on scraps of paper. This was a creative retreat for the director, and he came here to find inspiration, the manager said brightly. I happened to be carrying a few of the books I had authored, so I scattered them around the room, and put some in the dresser drawers, hoping Francis might find something he liked and give me a call. I’m still waiting.

So, here, too, I have a couple of my books, and I slip one into the bureau drawer. You never know.

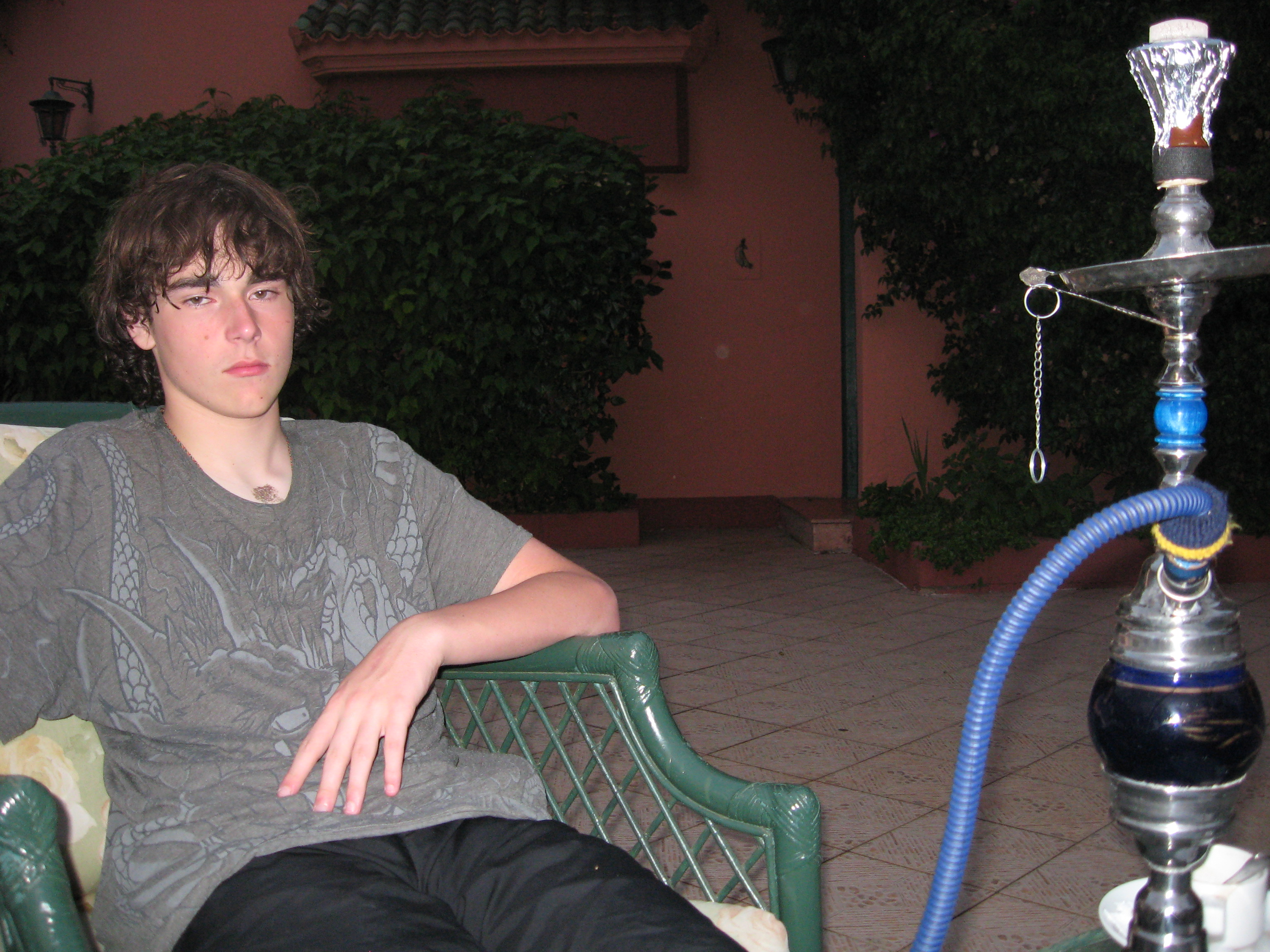

The day following we make the five hour drive from Tangier to the village of Chefchaouen (which means “look at the peaks”). Along the way we stop and Walker enjoys a number of “firsts,” his first camel ride, his first cup of coffee, and his first “monkey shower,” when a road-side handler places the primate on Walker’s shoulder for a photo op. One “first” he refuses is a hookah suck. At the back of a roadside café curved like the shell of a snail, men are drawing conspiratorially on giant hubble-bubble pipes, and so I order up one with two hoses. When it arrives I show him how it works, and the water gurgles, as a cloud of smoke curls the air. But Walker declines the cool smoke, and orders a Coke instead.

We pass cork forest and olive groves, soaring brick minarets trimmed with white, flocks of black goats and off-white sheep, and most provocative to Walker’s eye, shepherdesses in scarlet hats, white tops, boots and bright red knickerbocker leggings.

The sun is burning low and coppery when we pass through the Bab el-Majorrol gate into Chefchaouen, which happens to be a sister city of Issaquah, Washington, where I enjoyed many a hike when I lived in adjacent Redmond, and the two towns, I must say, would seem to have little in common. Up a steep, steep hill we grind, the engine sounding like a spoon caught in a disposal. We pull into the Atlas Riad Chaouen, nestled in a saddle beneath the stark limestone rock face of Ain Tissemlal (3280′) and Jebel el Kelaa (4206′), known together as Ech-Chaoua (the horns). Though in the shadow of these peaks, the hotel at the same time hangs high above the village, like the lair of a Doctor Seuss character. We drop our bags in the room, which is filled with the swish of the wind from the eucalyptus trees outside the single window. We pull back the curtains and are dazzled by a flood of canary yellow light. But when our eyes adjust we gape at a view of medieval houses whitened with a bluish lime — the walls shine in the sun like a glacier.

Walker is restless, and wants to stretch legs, so we decide to take a short hike to the ruins of a 250-year-old Portuguese mosque on a slope across the main river valley. It’s a hot hike, but it feels cooler for the long view from the crumbling tower across the river to the medina. Try to imagine the coolest, most mouth-wateringly liquid blue you’ve ever wanted to drink or dive into on a hot day: the homes in Chefchaouen are painted that color.

On the way back to the hotel we thread through the eastern gate of the medina, Bab el-Ansar, into the compact, cobalt blue-washed world via its steep and maze-like walkways. Even the stairs are dyed soft blue or cream. It makes the ice cream for sale from little carts irresistible, and we indulge in some soupy blue scoops on cones. Then we divagate the worn cobbled alleyways, some so narrow Walker’s long outstretched arms can touch both walls. We pass beneath tiny balconies, past little shops selling woven blankets, cedar wood antiques, necklaces of silver and red coral, and fennec furs. The tea houses are crowded but breezy with chat and brews. No cell phones here; just a cool, serene atmosphere. Blue is the overriding color; there is no seam between building and the sky…it’s like walking along the bottom of a resort pool.

Originally a fortress town, Chefchaouen was founded in 1471 to halt the advance of the Iberians after their capture of Ceuta to the north (still a Spanish protectorate), and served as a religious sanctuary for Muslims and Jews absquatulating from Granada. A series of dynasties ruled the area, long a center for Sufi mysticism, and the ‘zouia’ brotherhoods still practice their rites and traditions today. Access for Christians, however, was only gained in 1920, when Spanish troops occupied northern Morocco. Before then, the tourist brochure trumpets, only three westerners had ever visited this secret base. The invading Spanish found a time capsule of their own culture.

Now, Hispano-Moorish influence is apparent everywhere: in the clematis-covered archways that span the streets, in the narrow barred windows, and in the studded doorways that open onto sun-drenched patios. The singularly most stunning elements, however, are the blue painted buildings, soaked in different shades of turquoise and azure, producing a semi-mirage effect. The blue wash only came about in the 1930s, when Jewish refugees finally decided to paint over the previously Muslim-green window frames and doors.

Thirsty, we agree to sit and sip glasses of mint tea at one of the shops, one cluttered with treasure, and weighed down by a mountain of bargains. There are ancient Berber chests, silver teapots, ebony footstools, and weapons once used by warring tribes. Walker’s eyes brighten, and he soon finds himself tangled in the art of negotiating. He has the habit of rationing his conversation, which works to his advantage, as when his silences are long, the salesman breaks the quiet by punching his pocket calculator and lowering his price. Walker ends up buying an antique pistol for $30… the opening price was $3000, so he feels pretty trick about the deal, even though the salesman claims the firearm is older than gunpowder. I submit to a couple of kelims, the short rugs originally made to cushion the knees of the devout when they prayed towards Mecca, but now lining the walls and hallways of the infidels in the west. With our bootie in hand we head back up the hill, beads of sweat popping off our brows like insects. We pass a line of women in red and white striped overskirts and large conical straw hats with woolen bobbles, and they seem cool as cucumbers despite the heat. We beat it back to the hotel, which though modest in most regards, is generous in its air conditioning, and we sit back and enjoy the arctic air.

Almost nobody speaks English here — Arabic and Spanish are the lingua francas — which is in a way refreshing, and it prompts Walker and me to talk in ways we don’t when in restaurants back home. We point to items on the menu, and the waiter hovers like a black and white butterfly, nods, and then flits away. When he returns he serves us in a way that seems almost protective, as though there is a religious dimension to the hospitality, to the supper and succor for strangers.

After dinner I importune the front desk manager, who does speak a crumb of English, if he can help us find a guide to take us climbing tomorrow. “Ah, you want to go up our mountain… here we call it Mount Baldy” he informs, and Walker pulls off my hat and chuckles that it is the appropriate mountain for me.

“Yes. Can you find us a good guide?”

“Of course; the best. Be here in the lobby at 10:00 am.

“Isn’t that a bit late? Its summer…it gets hot. Shouldn’t we start quite early to avoid the midday heat while hiking?

“No, no… you will be fine. Besides my guide doesn’t start before 10:00.”

The sky lightens slowly the next morning, and time seems to pour like treacle as we linger through breakfast. At last, about 10:30 Moroccan Time, Anass Hazim, 27, saunters into the lobby and extends his hand. His skin is parched and rough and feels like the hand of a reptile. He tells us he has been a guide for seven years, and has climbed Mount Baldy many times — we have nothing to worry about. It should take a nice and easy three hours for the whole enterprise. But I am a little leery of his leather leisure shoes, even if it is but a stroll. I ask about water, and he says, not to worry, we won’t need any. But that doesn’t feel right, so I quickly buy four plastic bottles of Sidi Ali water from the restaurant and stuff them into my pack. He piles us into a car, and we drive through twenty shades of moonscape into the Parc National de Talassemtane, to a settlement called Akchour. At the foot of a low dam on the river Kelaa we park. The surrounding mountains are all burnt umber and dusty taupe, scarred with horizontal serrations, jutting up in every direction. Here we shoulder our packs, and start walking up the side of the river, past oleander bushes, through stands of Holm oak and feathery pines, and alongside steep cliffs. It’s steep and hot, following the contours of the gorge, so hot it sends chills down my arms. Walker and I each swallow a bottle of water in the first hour. I’m a little surprised to note that Anass doesn’t wear sunglasses or a hat, and to see that he smokes constantly, but perhaps that is the norm in Morocco. Our guide in the Atlas, Rachid, did as well. But there is something about Anass that doesn’t quite seem guide-like. His eyes are not far-reaching as are the eyes of most of the wilderness guides I have known. He seems to focus more on the surface of the present.

About noon we come to a natural stone arch that crosses the river, the Pont de Dieu or “God’s Window,” and here Walker announces he doesn’t want to go any farther. He wants to wait here in the shade by the bridge.

“It’s too hot, Dad.”

I’m okay with that, and since it must only be a short walk from here to the top, I figure we will be up and back in an hour. But Anass doesn’t want to go any farther either.

“Why not?” I ask. “You’re the professional mountain guide.”

He draws his face into hundreds of little wrinkles, not in a squint, but as if his face is drawing inward to escape a truth.

“I have not guided beyond here before….only to the bridge”

“What?”

“Tourists don’t go past here.”

“Well, I am…you have to come with me…you’re the guide.”

So, I leave a bottle of water with Walker, and tuck the last one in my fanny pack for easy access, and Anass and I start the steep climb. It is a faint trail, zigzagging through the cedars and brush, and after a few minutes I can look up and see what looks like the summit. But suddenly Anass stops.

“We must turn around.”

“I don’t understand. Why? We can see the top.”

“No, that is not the top…there are four more peaks beyond that to the summit, and you have to go up and down steep valleys. It will take three days.” He gives me a glaze like the gleam off a knife.

“But you said three hours.”

“It is too dangerous to continue. It is a technical climb.”

“What do you mean? We’re on a path…let’s keep going.”

I turn and start to hike and Anass follows me grudgingly. I stop after a few minutes, and take a draw on the water bottle, and offer some to Anass…his brow is glistening with sweat as he takes a long drink, and then announces he is turning back.

“You can’t turn back…you are my guide.”

He clearly isn’t gripped with this idea.

“You must turn back with me…there are wild Barbary apes near the top…they will attack you. I know this.”

This gives me pause…the image of fending off a troop of wild macaques, alone on a hot mountain, is not favorable. But I catch myself…this can’t be true.

“I’m going on Anass even without you.”

He screws up his face until his eyes are no more than slits.

“You should not. If I get into trouble that is okay; but if you get into trouble, it is a big problem for me.”

“I’m sorry Anass….you go check on Walker. I’ll hike to the top, and be back soon.”

He gives me a gimlet glare, then turns on his heel and heads down the hill.

I realize now how brutal the sun is… it is midday, and there is no shade as I continue. But I am convinced it is but a short ways to the summit, and then I can turn back and reunite with Walker and the river.

But as I get closer to the top it seems to roll away, as though on wheels. And then the trail careens off to the side…I follow it, and it takes me over a shoulder that reveals another peak higher than what I had been watching. But it is not so far, so I continue. And I take judicious sips from my water bottle.

After another 30 minutes of hiking I breach another pass, and see there is still another higher peak. I weigh the options, wipe my brow, and decide it’s better to continue…it can’t be that much farther.

But it is…I struggle up a steep section, and rise to another false summit, and stare at a new, higher summit, but this one is across a wide and deep valley. It does look as though it might take days to traverse this route. Anass was right. But the good news, I tell myself, is there are no Barbary Apes in sight.

So, I take a long draw from my plastic bottle, and begin the return hike, now most certainly not overburdened with an abundance of water. Along the way I notice something I had missed coming up… discarded clothing. There is a pair of blue socks; a while later, a sweater. And then at a sharp bend in the path, a pair of trousers. What happened here, I wonder, that people abandoned their clothes on this trail?

It is getting hotter. The heat is rippling, like just out of a kiln. I stop every hundred yards or so and try to rest in the scant shelter of a scrawny cedar. I pull a branch from the tree — it smells like soap — and turn it into a hiking stick. I take the last few sips of water.

Then I start to feel the onset of heat exhaustion: dizziness, muscle weakness and nausea. My throat is dry; my lips cracked. The heat bites at the corners of my eyes. I feel a sweat fever coming on, though I feel no sweat. In a landscape as this one can sweat four gallons a day without realizing it. The sweat evaporates too quickly to be noticed.

I know what happens next….the throat constricts, the body temperature soars. Disorientation, hallucinations, gagging and liver failure follow, and then coma and death. On the upside, I could qualify for a Darwin Award.

The sky is anything but sheltering here, but Paul Bowles would appreciate this setting, I believe. He derived his most famous title from a popular World War I tune, “Down Among the Sheltering Palms.” Because in the Sahara there is only the sky, Bowles omitted the palms, leaving the fine fabric of the sky. Bowles presented the new conditions of modernity, ground rules for the infidel: the sky is the thin membrane between life and death, the traveler’s final frontier, and the last obstacle to repose.

I stop and sit on a lozenge of stone for a spell, and watch as a high-tufted Houbara bustard lands on a crag and struts about. I envy the bird. I want to fly. No, I want to rest, and lower my head into my lap. I can feel my body wilt and meeken. I fight for clarity in the mayhem of my mind. I curl into a little ball with my arms wrapped tightly around my knees and become a pebble on this path. I am, at this place, at this time, unessential to the world. But then I shake my head vigorously, and pull myself up leaning on my stick. I know I have to continue. I’m out of water, and there are no other people on this trail in the summer heat of the Riff. I pull out my cell phone, but there is no service.

So, downwards I stagger, my legs making long steps as if of their own accord. Had I jockeyed my horse into a flaming barn, I wonder? The faint path seems to divide into three, and I take the left one, as I lean that way. But after a time it peters out, and I am thrashing through sharp scrub. I’m lost. This is not the “lost” of the Fès medina. This is a lost that could have serious consequences in short order. I turn around and scrape back up the hill to the tracings of the path, and take the middle way.

After a spell I think I am beginning to hallucinate. I see a pond, and walk towards it, but it wavers away. I think I see a woman hiker and yell to her, but as I get closer I see she has the feet of a goat. She must be Aisha Qandisha, the Moroccan siren who lures people to their doom, causes uncontrollable ecstasy and ultimately destructive obsession. But as I warily move towards her she turns into a tree. I am accompanied only by myself. Having worked as a guide on the Grand Canyon, I know the dangers of heat exhaustion, and I recognize that I am sliding into a dodgy state. But what is the choice?

What was I thinking taking this trek alone in the midday sun? I am not Thesiger and his Bedouin, but a lesser mortal who has spent most of my adventuring on water. Now I am without my favored element, and suffering for it.

It is said that a Sufi dervish wanders the earth because the action of walking dissolves the attachments of the world, and that his aim is to become a “dead man walking,” a man whose feet are rooted on the ground but whose spirit is already in Heaven. I wonder if I am at this moment a dead man walking, though I can barely take a step, so perhaps it is a dead man stumbling.

At last I see the Kelaa canyon rim, I think… it wobbles rubbery in the heat. I disbelieve my eyes, and strain to refocus them… But the precipice is real, and though it feels as though every molecule of moisture has been sucked out of me, the sight gives me another wind. I totter and lurch downwards, mentally munching nothingness. In most circumstances a bridge is a good trek spoiled, but here it is nirvana. I spy the span, and Walker standing waving back at me. I make it to the bridge, and give Walker a hug, and then find a spot to lay down in some shade. Anass stands above me, his mouth turned down at the corners like a cartoon. He grabs a palm-frond and waves it around my face, like an Orthodox priest blessing me with his thurible. Walker grabs my hand and fixes me with his eyes.

“Dad, I was getting worried… and wanted to call for help, but cell phones don’t work here.”

I can only grimace… my tongue is gluey with shame; my lips round to form my son’s name, but no sound comes forth. My lips feel like dry corn husks chaffing against each other. I feel as though the sun had ruthlessly charged through my body, and left something less than before. It burned my outer layer and left me floating numb, a derelict shell.

Walker fetches me the last of his water, and I drink it greedily. But my throat cries for more. Walker gently pries the water bottle from my rigid fingers. Anass tells me I was gone for four hours, and that he was about to head down to Akchour to find a landline and call for a rescue team.

I take a long rest, and Walker and Anass fetch more bottles of water, which I down as though they are miniatures. Then, with Walker helping me I slowly make my way down the path, like a battle-wounded soldier on retreat. When we get to the Akchour reservoir, both Walker and I pull off our clothes, and jump into the cold, cold waters. There is an overwhelming feeling of Tissir, an untranslatable Arabic word for a state of bliss and luck.

That evening, back in the powder-blue cocoon that is Chefchaouen, we all take dinner at an open-air restaurant in the Plaza Uta el-Hamman, across from toffee-colored walls of the 18th century Kasbah. The legendary ruler Moulay Ismail built this Kasbah, but it is most noted for the hardheaded local chief, Abdu l-Karim, who was imprisoned within the walls in 1926 by Spanish troops. With his fall, the Spanish took over and held northern Morocco for the next 30 years. Now, it is a garden and a tourist attraction.

Between bites of our goat-meat tajine, washed down with freshly-squeezed orange juice (alcohol is prohibited here, though not apparently kif, which grows in abundance in fields surrounding the village), I ask Anass why he lied to me about so many things.

“You are strong, Mr. Richard. But as a guide, as a Moroccan, I was worried about you. I watched you the first hour, and saw someone more proud than wise. I did not think you would listen to my ideas. So, I tried to turn you around. These were my ways. I am sorry.”

But I was glad to be alive, dining in a blue cloud, across from a Kasbah. Like the nomad, when there is no more, it is time to leave.

Sounds like a very cultural place! My Mum has been to Morocco and I would love to go and see where they filmed scenes from Star Wars! You really are a wonderful writer. Thanks for sharing. Craig